Music WireTwo revolutions in piano development

Two revolutions in piano development

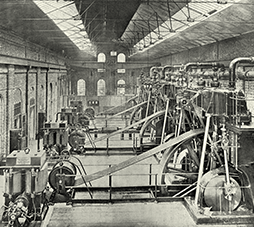

The piano was originally an instrument for the enjoyment of aristocrats. However, in the latter half of the eighteenth century, a new middle class emerged, enriched by the Industrial Revolution. Known as the bourgeoisie, they bought pianos as a symbol of their newly elevated status in society. As a result, demand for pianos increased rapidly. Small-scale workshop production was insufficient to keep up with demand, and piano makers scaled up to mass production at larger facilities. At the same time, with aristocracy generally in decline, marked by events like the French Revolution, many musicians lost their wealthy patrons and turned to the masses, where they found a large and ready audience. Piano music moved from the salon to the concert hall. This drove new changes in the piano, calling for increases in range and volume, which were achieved by harnessing the technological advances of the new age of industry. So many improvements were made during this time that it's said that the highest number of patent applications were in the field of piano making. At this point, the prototype of the modern piano was nearly complete.

The following are but some of the notable milestones in the evolution of piano strings.

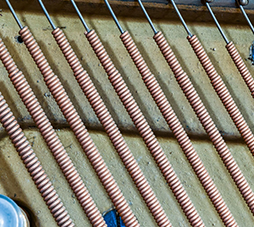

- 1785-1815: Windings are adopted for the bass strings of square pianos.

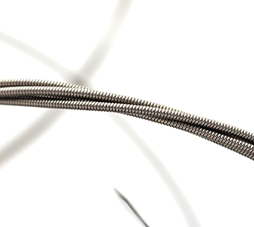

- 1819: Blockdon invents diamond and ruby wire-pulling dies. The first wire made with these dies is used for the strings of Broadwood pianos.

- 1826: Jean-Henri Pape begins using higher-strength strings.

- Around 1830: Webster of Birmingham, UK, develops steel strings.

- 1835: Boehme uses overwound steel wire for bass strings.

- 1854: Horsfall of the UK patents a heat treatment process for strengthening piano wire.

- 1893: Piano strings by Pollmann of Nuremburg win an award at the Chicago World's Fair.

A number of websites and print materials have stated that Steinway & Sons of the US acquired a patent for double winding in 1859. However, this appears to be an error, possibly arising from the company's 1859 patent for the "overstrung" arrangement of bass and treble strings common in most pianos today. Perhaps most important was the switch from brass and iron to higher strength steel wires, which increased the volume of the sound significantly. A comparison of the tensile strengths of brass, iron and steel wire is shown here.

| Materials | After heat treatment | After drawing, approximately 80% |

| Brass | 320~380MPa | 650~800MPa |

| Iron wire (low-carbon) | 440~550MPa | 850~1050MPa |

| Steel wire (high-carbon) | 1100~1300Mpa | 2400~2600MPa |

Steel wire can be made much stronger than brass or iron wire. But the amount of carbon incorporated in iron and steel is different, and it is more challenging to manufacture high-carbon steel wire than low-carbon iron wire. The exact point at which the modern standard of steel music wire began to be used in pianos is uncertain, but from the above chronology we can assume that it was between 1820 and 1830. The introduction of the patented heat treatment process in 1853 was especially important, as it made it significantly easier to manufacture piano wire from high-carbon steel, which enabled much higher tension on the piano strings. The development of this material and the heat treatment process had a major influence on the evolution of the piano body as well. The following data shows the transition in the strength of piano strings in the latter half of the 19th century. Both wire diameters are 0.77 mm at number 13.

| Age | Tensile strength |

| 1867 | 2148MPa |

| 1873 | 2216MPa |

| 1876 | 2530MPa |

| 1884 | 2638MPa |

| 1893 | 3099MPa |

Although the 1893 data may be questionable in terms of current industrial standards, it can be seen as representative of the material that won Pollmann the prize at the Chicago World's Fair that year. Today, No. 13 music wire has a wire diameter of 0.775 mm and the tensile strength is typically 2400 to 2610 MPa, so you can see that there was already something comparable to the current standard in the 1870s.

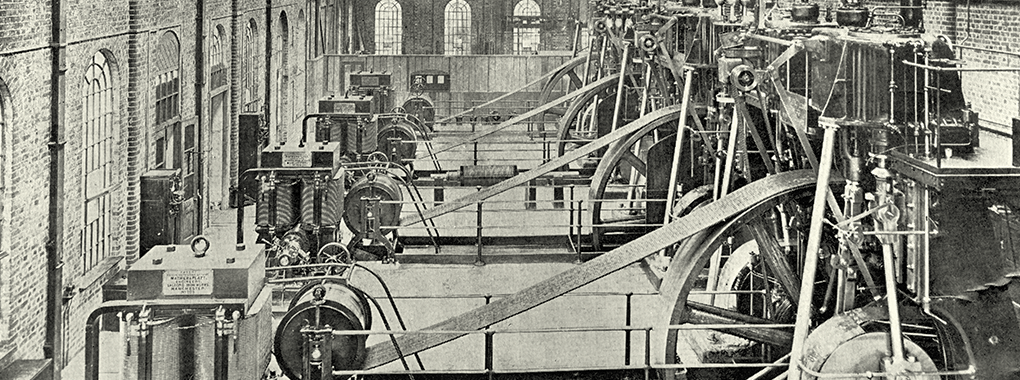

As stronger piano wire allowed more tension to be put on the strings, the increased load became more than could be supported by the conventional wooden frame. Some form of reinforcement or more dramatic measure was required. In 1799, Joseph Smith of the UK acquired a patent to reinforce the wooden frame with a metal strut, which would lead to the adoption of a full metal frame. In 1825, Alpheus Babcock of the US devised and acquired a patent for a single cast iron frame. Although Babcock was an excellent technician, he was not as well suited to managing his own firm, and in 1837 he began to work at Chickering & Sons, a piano maker in Boston. In 1840, Chickering applied for a patent for a grand piano design that adopted an integral cast iron frame. This was probably Babcock's concept. The patent was granted in 1843, but unfortunately he died that same year.

Casting is well suited for making intricate shapes and complex curves. Cast iron has other technical advantages as well, such as a high attenuation rate and resistance to resonance. The new technology invented by Babcock was actively adopted by a new generation of piano manufacturers Steinway, Bluthner, Bechstein and others which appeared one after another at that time. It also led to the adoption of overwound strings, as well as over- or cross-stringing a method of slanting the long strings of the bass section diagonally above the strings of the tenor and treble sections, making full use of the new frame characteristics. This trend spread to other long-established European manufacturers such as Streicher and Bosendorfer.

Square piano made by Babcock with cast iron frame

The simple combination of curves is beautiful. In contrast to the interior, the front appears massive. The American square piano of this time has a much heavier design than those designed and built in Europe.

Production: Babcock (1832-1837))

Source: PIANO 300

Incidentally, the total string tension on a piano in 1808 was 4.5 tons, but by 1850 this had increased to 12 tons, as the cast iron frame enabled the stretching of stronger high-carbon steel strings. The overall tension generated on a piano today can be as much as 20 tons, as we mentioned earlier, and the frame itself is designed to endure a load of 35 tons or more.

Cast iron frame for modern grand piano

Its dynamic and delicate form sets it apart from conventional industrial castings.

Photo provided by Yamaha Corporation